- Prayer

- Worship: “King of Glory” by CeCe Winans, “Praise You in this Storm” by Casting Crowns, “Don’t stop Praying” by Matthew West

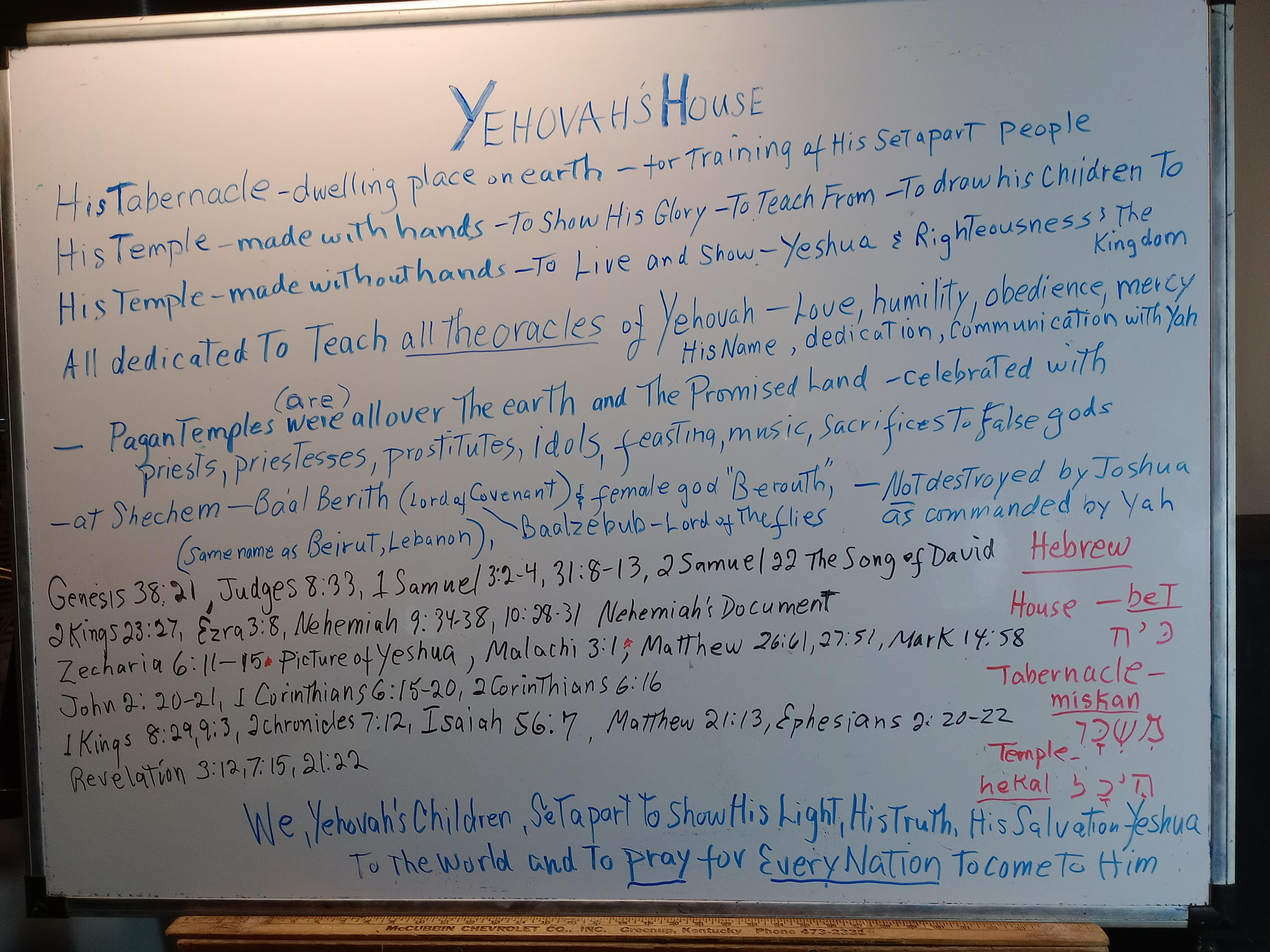

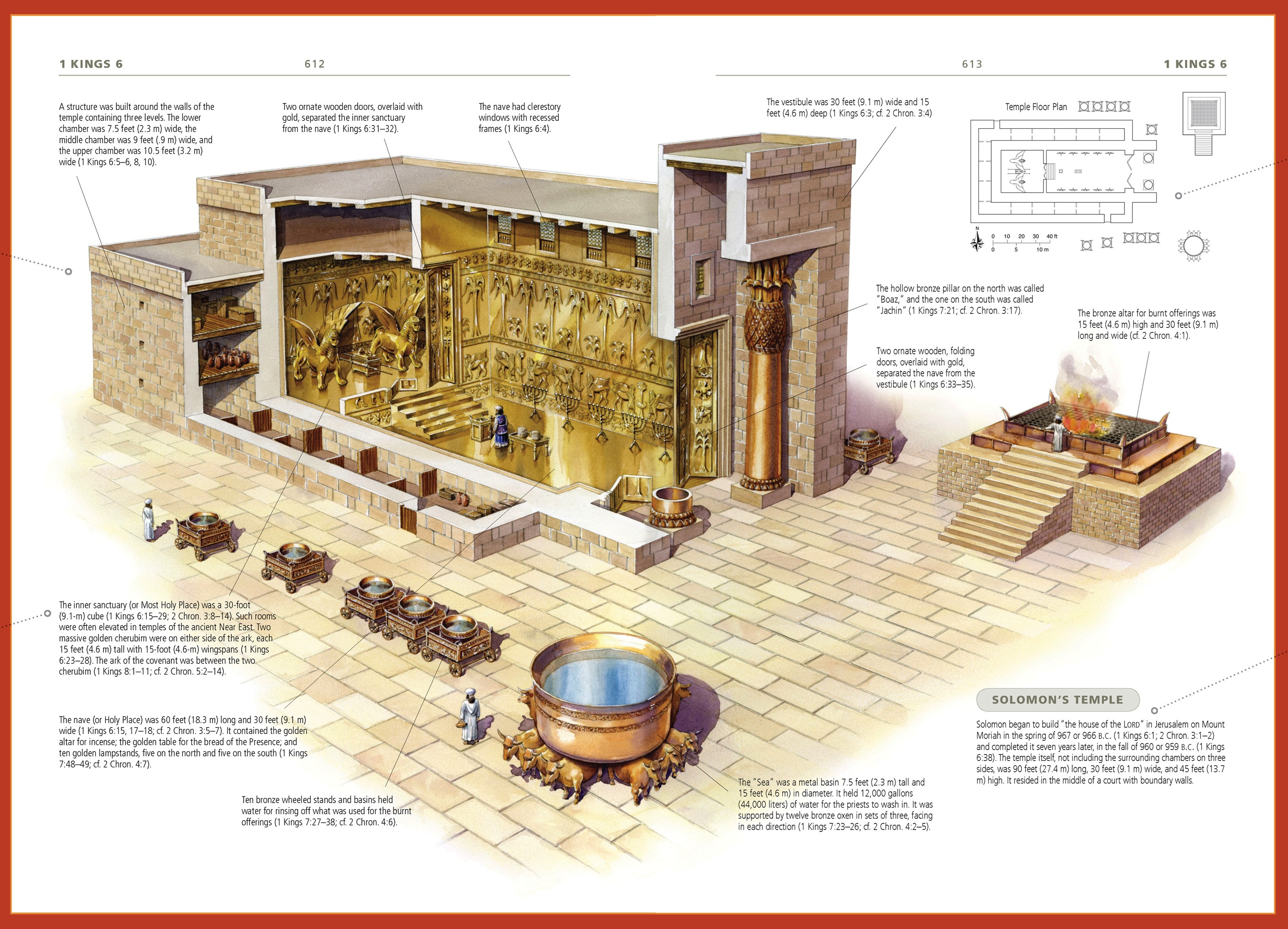

- Word study: Yehovah’s House

- Torah study: Numbers 18-19,

- Song: “Come, Jesus Come” by Stephan Mcwhirter

All These Things Added

by James Allen

Every phenomenon in social and national life (as in Nature) is an

effect, and all these effects are embodied by a cause which is not

remote and detached, but which is the immediate soul and life of the

effect itself. As the seed is contained in the flower, and the flower in

the seed, so the relation of cause and effect is intimate and

inseparable. An effect also is vivified and propagated, not by any life

inherent in itself, but by the life and impulse existing in the cause.

Looking out upon the world, we behold it as an arena of strife in which

individuals, communities, and nations are constantly engaged in

struggle, striving with each other for superiority, and for the largest

share of worldly possessions.

We see, also, that the weaker fall out defeated, and that the strong —

those who are equipped to pursue the combat with undiminished ardour —

obtain the victory, and enter into possession. And along with this

struggle we see the suffering which is inevitably connected with it —

men and women, broken down with the weight of their responsibilities,

failing in their efforts and losing all; families and communities broken

up, and nations subdued and subordinated.

We see seas of tears, telling of unspeakable anguish and grief; we see

painful partings and early and unnatural deaths; and we know that this

life of strife, when stripped of its surface appearances, is largely a

life of sorrow. Such, briefly sketched , are the phenomena connected

with that aspect of human life with which we are now dealing; such are

the effects as we see them; and they have one common cause which is

found in the human heart itself.

As all the multiform varieties of plant life have one common soil from

which to draw their sustenance, and by virtue of which they live and

thrive, so all the varied activities of human life are rooted in, and

draw their vitality from, one common source—/the human heart/. The cause

of all suffering and of all happiness resides, not in the outer

activities of human life, but in the inner activities of the heart and

mind; and every external agency is sustained by the life which it

derives from human conduct.

The organized life-principle in man carves for itself outward channels

along which it can pour its pent-up energies, makes for itself vehicles

through which it can manifest its potency and reap its experience, and,

as a result, we have our religious, social and political organizations.

All the visible manifestations of human life, then, are effects; and as

such, although they may possess a reflex action, they can never be

causes, but must remain forever what they are—/dead effects/, galvanized

into life by an enduring and profound cause.

It is the custom of men to wander about in this world of effects, and to

mistake its illusions for realities, eternally transposing and

readjusting these effects in order to arrive at a solution of human

problems, instead of reaching down to the underlying cause which is at

once the centre of unification and the basis upon which to build a

peace-giving solution of human life.

The strife of the world in all its forms, whether it be war, social or

political quarrelling, sectarian hatred, private disputes or commercial

competition, has its origin in one common cause, namely,/individual

selfishness/. And I employ this term selfishness in a far-reaching

sense; in it I include all forms of self-love and egotism— I mean by it

the desire to pander to, and preserve at all costs, the personality.

This element of selfishness is the life and soul of competition, and of

the competitive laws. Apart from it they have no existence. But in the

life of every individual in whose heart selfishness in any form is

harboured, these laws are brought into play, and the individual is

subject to them.

Innumerable economic systems have failed, and must fail, to exterminate

the strife of the world. They are the outcome of the delusion that

outward systems of government are the causes of that strife, whereas

they are but the visible and transient effect of the inward strife, the

channels through which it must necessarily manifest itself. To destroy

the channel is, and must ever be ineffectual, as the inward energy will

immediately make for itself another, and still another and another.

Strife cannot cease; and the competitive laws /must prevail so long as

selfishness is fostered in the heart/. All reforms fail where this

element is ignored or unaccounted for; all reforms will succeed where it

is recognized, and steps are taken for its removal.

Selfishness, then, is the root cause of competition, the foundation on

which all competitive systems rest, and the sustaining source of the

competitive laws. It will thus be seen that all competitive systems, all

the visible activities of the struggle of man with man, are as the

leaves and branches of a tree which overspreads the whole earth, the

root of that tree being individual selfishness, and the ripened fruits

of which are pain and sorrow.

This tree cannot be destroyed by merely lopping off its branches; to do

this effectively, /the root must be destroyed/. To introduce measures in

the form of changed external conditions is merely lopping off the

branches; and as the cutting away of certain branches of a tree gives

added vigour to those which remain, even so the very means which are

taken to curtail the competitive strife, when those means deal entirely

with its outward effects, will but add strength and vigour to the tree

whose roots are all the time being fostered and encouraged in the human

heart. The most that even legislation can do is to prune the branches,

and so prevent the tree from altogether running wild.

Great efforts are now being put forward to found a “Garden City,” which

shall be a veritable Eden planted in the midst of orchards, and whose

inhabitants shall live in comfort and comparative repose. And beautiful

and laudable are all such efforts when they are prompted by unselfish

love. But such a city cannot exist, or cannot long remain the Eden which

it aims to be in its outward form, unless the majority of its

inhabitants have subdued and conquered the inward selfishness.

Even one form of selfishness, namely, self-indulgence, if fostered by

its inhabitants, will completely undermine that city, levelling its

orchards to the ground, converting many of its beautiful dwellings into

competitive marts, and obnoxious centres for the personal gratification

of appetite, and some of its buildings into institutions for the

maintenance of order; and upon its public spaces will rise jails,

asylums, and orphanages, for where the spirit of self-indulgence is, the

means for its gratification will be immediately adopted, without

considering the good of others or of the community (for selfishness is

always blind), and the fruits of that gratification will be rapidly reaped.

The building of pleasant houses and the planting of beautiful gardens

can never, of itself, constitute a Garden City unless its inhabitants

have learned that self-sacrifice is better than self-protection, and

have first established in their own hearts the Garden City of unselfish

love. And when a sufficient number of men and women have done this, the

Garden City will appear, and it will flourish and prosper, and great

will be its peace, for “out of the heart are the issues of life.”

Having found that selfishness is the root cause of all competition and

strife, the question naturally arises as to how this cause shall be

dealt with, for it naturally follows that a cause being destroyed, all

its effects cease; a cause being propagated, all its effects, however

they may be modified from without, /must/ continue.

Every man who has thought at all deeply upon the problem of life, and

has brooded sympathetically upon the sufferings of mankind, has seen

that selfishness is at the root of all sorrow—in fact, this is one of

the truths that is first apprehended by the thoughtful mind. And along

with that perception there has been born within him a longing to

formulate some methods by which that selfishness might be overcome.

The first impulse of such a man is to endeavour to frame some outward

law, or introduce some new social arrangements or regulations, which

shall put a check on /the selfishness of others/.

The second tendency of his mind will be to feel his utter helplessness

before the great iron will of selfishness by which he is confronted.

Both these attitudes of mind are the result of an incomplete knowledge

of what constitutes selfishness. And this partial knowledge dominates

him because, although he has overcome the grosser forms of selfishness

in himself, and is so far noble, he is yet selfish in other and more

remote and subtle directions.

This feeling of “helplessness” is the prelude to one of two

conditions—the man will either give up in despair, and again sink

himself in the selfishness of the world, or he will search and meditate

until he finds another way out of the difficulty. And that way he will

find. Looking deeper and ever deeper into the things of life;

reflecting, brooding, examining, and analysing; grappling with every

difficulty and problem with intensity of thought, and developing day by

day a profounder love of Truth—by these means his heart will grow and

his comprehension expand, and at last he will realize that the way to

destroy selfishness is not to try to destroy /one form/ of it in other

people, but to destroy it utterly, root and branch, /in himself/.

The perception of this truth constitutes spiritual illumination, and

when once it is awakened in the mind, the “straight and narrow way” is

revealed, and the Gates of the Kingdom already loom in the distance.

Then does a man apply to himself (not to others) these words—/And why

beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest

not the beam that is in thy own eye? Or how wilt thou say to thy

brother, let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam

is in thine own eye? Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of

thine own eye; and then shall thou see clearly to cast out the mote out

of thine brother’s eye./

When a man can apply these words to himself and act upon them, judging

himself mercilessly, but judging none other, then will he find his way

out of the hell of competitive strife, then will he rise above and

render of non-effect the laws of competition, and will find the higher

Law of Love, subjecting himself to which every evil thing will flee from

him, and the joys and blessings which the selfish vainly seek will

constantly wait upon him. And not only this, he will, having lifted

himself, lift the world. By his example many will see the Way, and will

walk it; and the powers of darkness will be weaker for having lived.

It will here be asked, “But will not man who has risen above his

selfishness, and therefore above the competitive strife, suffer through

the selfishness and competition of those around him? Will he not after

all the trouble he has taken to purify himself, suffer at the hands of

the impure?”

No, he will not. The equity of the Divine Order is perfect, and cannot

be subverted, so that it is impossible for one who has overcome

selfishness to be subject to those laws which are brought into operation

by the action of selfishness; in other words, each individual suffers by

virtue of his own selfishness.

It is true that the selfish all come under the operation of the

competitive laws, and suffer collectively, each acting, more or less, as

the instrument by which the suffering of others is brought about, which

makes it appear, on the surface, as though men suffered for the sins of

others rather than their own. But the truth is that in a universe the

very basis of which is harmony, and which can only be sustained by the

perfect adjustment of all its parts, each unit receives its /own/

measure of adjustment, and suffers by and of itself.

Each man comes under the laws of his own being, never under those of

another. True, he will suffer like another, and even through the

instrumentality of another, if he elects to live under the same

conditions as that other. But if he chooses to desert those conditions

and to live under another and higher set of conditions of which that

other is ignorant, he will cease to come under, or be affected by, the

lower laws.

Let us now go back to the symbol of the tree and carry the analogy a

little further. Just as the leaves and branches are sustained by the

roots, so the roots derive their nourishment from the soil, groping

blindly in the darkness for the sustenance which the tree demands. In

like manner, selfishness, the root of the tree of evil and of suffering,

derives its nourishment from the dark soil of /ignorance/. In this it

thrives; upon this it stands and flourishes. By ignorance I mean

something vastly different from lack of learning; and the sense in which

I use it will be made plain as I proceed.

Selfishness always gropes in the dark. It has no knowledge; by its very

nature it is cut off from the source of enlightenment; it is a blind

impulse, knowing nothing, obeying no law, for it knows none, and is

thereby forcibly bound to those competitive laws by virtue of which

suffering is inflicted in order that harmony may be maintained.

We live in a world, a universe, abounding with all good things. So great

is the abundance of spiritual, mental and material blessings that every

man and woman on this globe could not only be provided with every

necessary good, but could live in the midst of abounding plenty, and yet

have much to spare. Yet, in spite of this, what a spectacle of ignorance

do we behold!

We see on the one hand millions of men and women chained to a ceaseless

slavery, interminably toiling in order to obtain a poor and scanty meal

and a garment to cover their nakedness; and on the other hand we see

thousands, who already have more than they require and can well manage,

depriving themselves of all the blessings of a true life and of the vast

opportunities which their possessions place within their reach, in order

to accumulate more of those material things for which they have no

legitimate use. Surely men and women have no more wisdom than the beasts

which fight over the possession of that which is more than they can all

well dispose of, and which they could all enjoy in peace!

Such a condition of things can only occur in a state of ignorance deep

and dark; so dark and dense as to be utterly impenetrable save to the

unselfish eye of wisdom and truth. And in the midst of all this striving

after place and food and raiment, there works unseen, yet potent and

unerring, the Overruling Law of Justice, meting out to every individual

his own quota of merit and demerit. It is impartial; it bestows no

favours; it inflicts no unearned punishments:

It knows not wrath nor pardon; utter-true

It measures mete, its faultless balance weighs;

Times are as nought, tomorrow it will judge,

Or after many days.

The rich and the poor alike suffer for /their own selfishness/; and none

escapes. The rich have their particular sufferings as well as the poor.

Moreover, the rich are continually losing their riches; the poor are

continually acquiring them. The poor man of today is the rich man of

tomorrow, and vice versa.

There is no stability, no security in hell, and only brief and

occasional periods of respite from suffering in some form or other.

Fear, also, follows men like a great shadow, for the man who obtains and

holds by selfish force will always be haunted by a feeling of

insecurity, and will continually fear its loss; while the poor man, who

is selfishly seeking or coveting material riches, will be harassed by

the fear of destitution. And one and all who live in this underworld of

strife are overshadowed by one great fear—the fear of death.

Surrounded by the darkness of ignorance, and having no knowledge of

those eternal and life-sustaining Principles out of which all things

proceed, men labour under the delusion that the most important and

essential things in life are food and clothing, and that their first

duty is to strive to obtain these, believing that these outward things

are the source and cause of all comfort and happiness.

It is the blind animal instinct of self-preservation (the preservation

of the body and personality), by virtue of which each man opposes

himself to other men in order to “get a living” or “secure a

competency,” believing that if he does not keep an incessant watch on

other men, and constantly renew the struggle, they will ultimately “take

the bread out of his mouth.”

It is out of this initial delusion that comes all the train of

delusions, with their attendant sufferings. Food and clothing are not

the /essential/ things of life; not the causes of happiness. They are

non-essentials, effects, and, as such, proceed by a process of natural

law from the essentials, the underlying cause.

The essential things in life are the enduring elements in

character—integrity, faith, righteousness, self-sacrifice, compassion,

love; and out of these all good things proceed.

Food and clothing, and money are dead effects; there is in them no life,

no power except that which we invest with them. They are without vice

and virtue, and can neither bless nor harm. Even the body which men

believe to be themselves, to which they pander, and which they long to

keep, must very shortly be yielded up to the dust. But the higher

elements of character are life itself; and to practice these, to trust

them, and to live entirely in them, constitutes the Kingdom of Heaven.

The man who says, “I will first of all earn a competence and secure a

good position in life, and will then give my mind to those higher

things,” does not understand these higher things, does not believe them

to be higher, for if he did, it would not be possible for him to neglect

them. He believes the material outgrowths of life to be the higher, and

therefore he seeks them first. He believes money, clothing and position

to be of vast and essential importance, righteousness and truth to be at

best secondary; for a man always sacrifices that which he believes to be

lesser to that which he believes to be greater.

Immediately after a man realizes that righteousness is of more

importance than the getting of food and clothing, he ceases to strive

after the latter, and begins to live for the former. It is here where we

come to the dividing line between the two Kingdoms—Hell and Heaven.

Once a man perceives the beauty and enduring reality of righteousness,

his whole attitude of mind toward himself and others and the things

within and around him changes. The love of personal existence gradually

loses its hold on him; the instinct of self-preservation begins to die,

and the practice of self-renunciation takes its place. For the sacrifice

of others, or of the happiness of others, for his own good, he

substitutes the sacrifice of self and of his own happiness for the good

of others. And thus, rising above self, he rises above the competitive

strife which is the outcome of self, and above the competitive laws

which operate only in the region of self, and for the regulation of its

blind impulses.

He is like the man who has climbed a mountain, and thereby risen above

all the disturbing currents in the valleys below him. The clouds pour

down their rain, the thunders roll and the lightnings flash, the fogs

obscure, and the hurricanes uproot and destroy, but they cannot reach

him on the calm heights where he stands, and where he dwells in

continual sunshine and peace.

In the life of such a man the lower laws cease to operate, and he now

comes under the protection of a higher Law—namely, the Law of Love; and,

in accordance with his faithfulness and obedience to this Law, will all

that is necessary for his well-being come to him at the time when he

requires it.

The idea of gaining a position in the world cannot enter his mind, and

the external necessities of life, such as money, food and clothing, he

scarcely ever thinks about. But, subjecting himself for the good of

others, performing all his duties scrupulously and without thinking of

reward, and living day by day in the discipline of righteousness, all

other things follow at the right time and in the right order.

Just as suffering and strife inhere in, and spring from, their root

cause, selfishness, so blessedness and peace inhere in, and spring from,

their root-cause, righteousness. And it is a full and all-embracing

blessedness, complete and perfect in every department of life, for that

which is morally and spiritually right is physically and materially right.

Such a man is free, for he is freed from all anxiety, worry, fear,

despondency, all those mental disturbances which derive their vitality

from the elements of self, and he lives in constant joy and peace, and

this while living in the very midst of the competitive strife of the world.

Yet, though walking in the midst of Hell, its flames fall back before

and around him, so that not one hair of his head can be singed. Though

he walks in the midst of the lions of selfish force, for him their jaws

are closed and their ferocity is subdued. Though on every hand men are

falling around him in the fierce battle of life, he falls not, neither

is he dismayed, for no deadly bullet can reach him, no poisoned shaft

can pierce the impenetrable armour of his righteousness. Having lost the

little, personal, self-seeking life of suffering, anxiety, fear, and

want, he has found the illimitable, glorious, self-perfecting life of

joy and peace and plenty.

“Therefore take no thought, saying ’What shall we eat?’ or, ’What shall

we drink?’ or, ’Wherewithal shall we be clothed? . . .’ For your

heavenly Father knoweth ye have need of all these things. But seek ye

first the Kingdom of God, and His Righteousness, and all these things

shall be added unto you.”